#285 - Pythagorean Odds

Albert chooses a positive integer $k$, then two real numbers $a$, $b$ are randomly chosen in the interval $[0, 1]$ with uniform distribution. The square root of the sum $(k\cdot a + 1)^2 + (k\cdot b + 1)^2$ is then computed and rounded to the nearest integer. If the result is equal to $k$, he scores $k$ points; otherwise he scores nothing.

For example, if $k=6$, $a=0.2$ and $b=0.85$, then $(k\cdot a + 1)^2 + (k\cdot b + 1)^2 = 42.05$. The square root of $42.05$ is $6.484\cdots$ and when rounded to the nearest integer, it becomes $6$. This is equal to $k$, so he scores $6$ points.

It can be shown that if he plays 10 turns with $k=1, k=2, \dots, k=10$, the expected value of his total score, rounded to five decimal places, is $10.20914$.

If he plays $10^5$ turns with $k=1,k=2,k=3,\dots,k=10^5$, what is the expected value of his total score, rounded to five decimal places?

- Background

- Redefining the problem statement

- Area under the circle

- Area of the full region under the circle

- Implementation

Background

This is an expected value problem with a unique setup. The randomness are on the coefficients $a$ and $b$, not on $k$. As a refresher, expected value for a certain random variable $X$ that takes on discrete values from $x=1$ up to $n$ is defined as \[\mathbb{E}(X) = \sum_{i=1}^n i P(x=i)\]

Basically, you multiply the value itself by the probability of attaining that value. Given $k$, we can only score exactly $k$ points or $0$ points. Thus, scoring $k$ points is the only event that will contribute to the expected value. Therefore, we can update our expected value formula to this problem: \[\mathbb{E}(X) = \sum_{i=1}^n k P(\text{scoring }k\text{ points})\]

The majority of this solution will be calculating that probability in the sum. We have two random distributions adjusting independently of each other. Because each of $a$ and $b$ are uniformly distributed between 0 and 1, we can represent this pictorally. Imagine a unit square, with side length 1, sitting in the Cartesian grid, with the bottom left corner at the origin. Having two uniformaly distributed random variables is akin to choosing a random point within this square. The $x$-coordinate represents our selection of $a$, and the $y$-coordinate represents our selection of $b$.

When representing probability in this way, calculating probability becomes a calculation an area. For example, $P\left(a\leq \frac{1}{2}\text{ and }b\leq \frac{1}{2}\right) = \frac{1}{4}$.

Redefining the problem statement

We have now introduced a visual representation for the random variable, and now we can continue that line of thinking. Let’s work with the main constraint algebraically. If the sum needs to eventually round to $k$, that means it needs to be in the interval $\left(k-\frac{1}{2}, k + \frac{1}{2}\right)$. Using inequalities, we can work with this as follows: \[\begin{aligned} k - \frac{1}{2} &< \sqrt{(ak+1)^2+(bk+1)^2} &< k + \frac{1}{2} \\ \left(\frac{2k-1}{2}\right)^2 &< (ak+1)^2 + (bk+1)^2 &< \left(\frac{2k+1}{2}\right)^2 \\ \left(\frac{2k-1}{2k}\right)^2 &< \left(a + \frac{1}{k}\right)^2 + \left(b + \frac{1}{k}\right)^2 &< \left(\frac{2k+1}{2k}\right)^2 \end{aligned}\]

Taking the boundary equations, we have the following two equations of a circle. \[\begin{aligned} \left(a +\frac{1}{k}\right)^2 + \left(b + \frac{1}{k}\right)^2 &= \left(\frac{2k-1}{2k}\right)^2 \\ \left(a +\frac{1}{k}\right)^2 + \left(b + \frac{1}{k}\right)^2 &= \left(\frac{2k+1}{2k}\right)^2 \end{aligned}\]

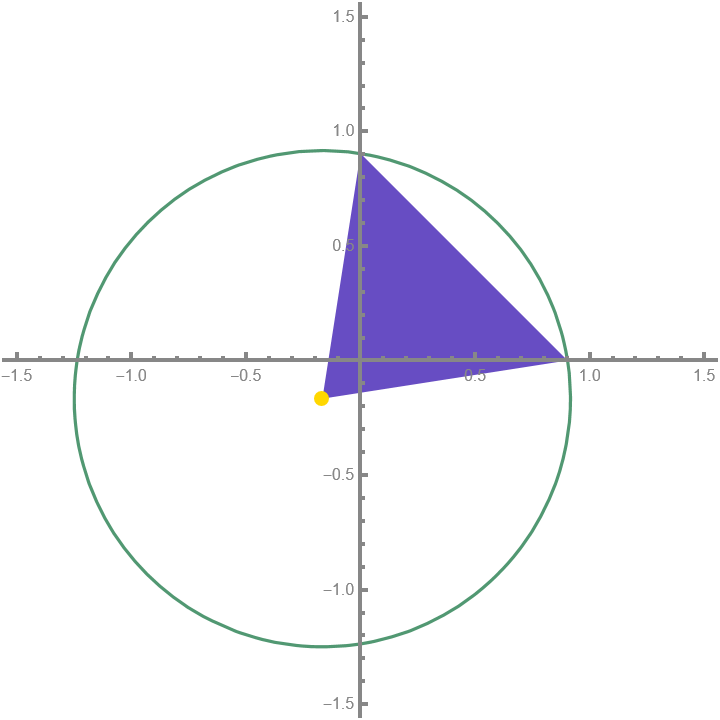

The first circle serves as our “lower bound” and the second circle is our “upper bound”. Writing in this way, we can graphically show the area we need to find.

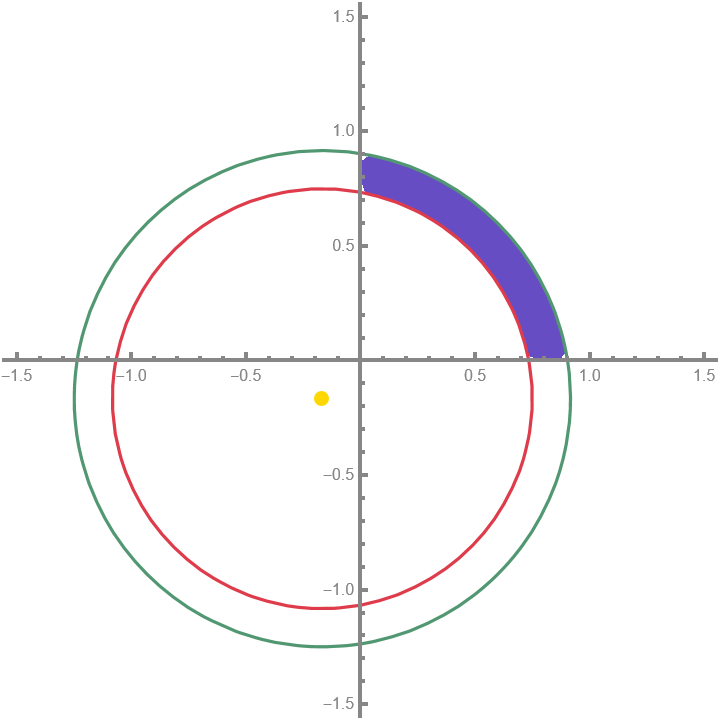

Plot of both circles at $k=6$. The blue shaded region shows the area we need to calculate. The yellow dot marks the center of both circles.

Since we have two circles, the area of the shaded region is simply the area under the big circle minus the area under the small circle.

Area under the circle

We will start with the larger circle, with radius $\frac{2k+1}{2k}$. Since both circles are scaled versions of each other, the formula will be extremely similar. There is also not a need for us to represent everything in terms of only $k$, since this will go into code.

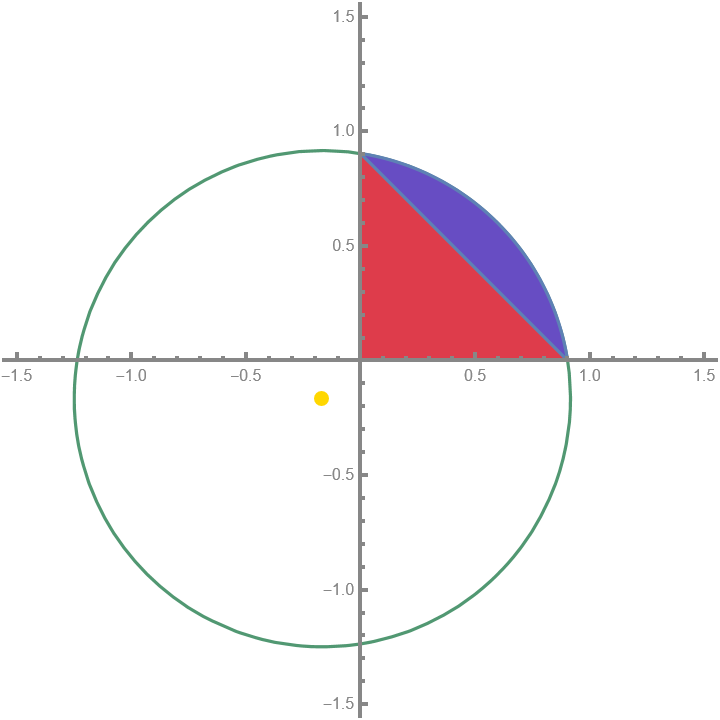

Note that the region is not a quarter circle! This is because the center is not at the origin. To find this area, we will break the region into two separate regions as follows:

Corresponding area broken into two separate regions.

We will tackle this one at a time, starting with the triangle region.

Area of triangle

The triangle is very well defined. One vertex is sitting at the origin, while the other two points are at the intersection points of the circle with the $a$ and $b$-axes (or $x$ and $y$ axes, if you prefer). Because the center is $\left(\frac{1}{k},\frac{1}{k}\right)$ and sitting on the line $b=a$, the right triangle is actually isoceles, and the nonzero value of the intersection points are the same. To find the intersection point $p$, we simply set either $a$ or $b$ in the original circle equation to 0, and solve for the remaining unknown. For example, with $a=0$, and solving for $b$ (or $p$ in this case), we have \[\begin{aligned} \left(\frac{1}{k}\right)^2 + \left(p+\frac{1}{k}\right)^2 &= r^2 \\ \left(p+\frac{1}{k}\right)^2 &= r^2 - \frac{1}{k^2} \\ p &= \boxed{\sqrt{r^2-\frac{1}{k^2}} - \frac{1}{k}} \end{aligned}\]

Of course, $p$ will be different depending on the radius of the circle. The triangle has coordinates $(0, 0)$, $(p, 0)$ and $(0, p)$. Thus, the base and height are both $p$, and thus, the area of the triangle is simply $\frac{1}{2}p^2$.

Area of the region

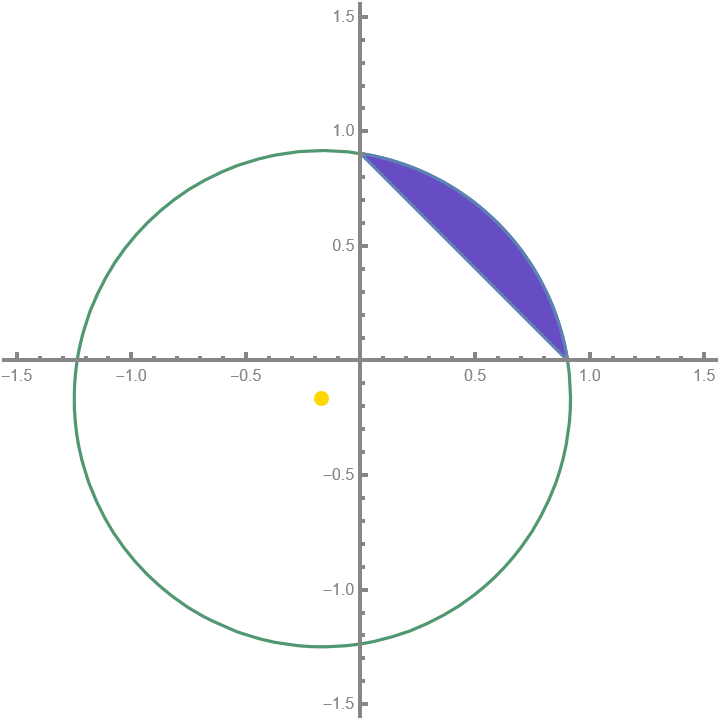

This region is a bit more tricky, but we can still calculate it using shapes whose areas we know how to calculate. We can observe that this region is the same as the area of the full sector (the “pizza slice”) with a triangle section taken out of it, as below.

The area of the small purple region is the difference between the full sector and the triangle whose vertex is at the origin.

We subtract the area of this large triangle from the area of the sector to find the area of the small region we need. To find the area of the full sector, we need to know the angle $\theta$ that it sweeps. Using the fact that two of the triangle’s sides are the radii, and the last side is the hypotenuse of the right triangle in the previous section, we can use the law of cosines to find $\theta$. Because the hypotenuse is part of a 45-45-90 triangle, the hypotenuse $c$ is exactly $i\sqrt{2}$. \[\begin{aligned} c^2 &= a^2 + b^2 - 2ab\cos\theta \\ 2i^2 &= 2r^2 - 2r^2\cos\theta \\ \cos\theta &= \frac{2r^2-2i^2}{2r^2} \\ \theta &= \boxed{\arccos\left( 1-\frac{i^2}{r^2} \right)} \end{aligned}\]

Thus, the area of the full sector is, \[A = \pi r^2\left(\frac{\theta}{2\pi}\right) = \frac{r^2\theta}{2}\]

Now for the triangle, where one of its veritces is sitting at the center of the circle. This triangle is a bit wonky, so how do we easily find the base and the height? Turns out, we don’t need to. It is possible to directly calculate the area of a triangle if you only know the side lengths. Heron’s formula utilizes all 3 side lengths, and the semiperimeter $s$. \[A = \sqrt{s(s-a)(s-b)(s-c)}\]

In our case, $a = b = r$, and $c = i\sqrt{2}$. Thus, $s = \frac{1}{2}(2r+i\sqrt{2}) = r + \frac{c}{2}$. Therefore, we have $s-a = s-b = \frac{c}{2}$ and $s-c=r-\frac{c}{2}$. Substituting in, we have \[\begin{aligned} A &= \sqrt{\left(r+\frac{c}{2}\right)\left(\frac{c}{2}\right)\left(\frac{c}{2}\right)\left(r-\frac{c}{2}\right)} \\ &= \frac{c}{2}\sqrt{r^2-\frac{c^2}{4}} \\ &= \frac{c}{2}\sqrt{\frac{4r^2-c^2}{4}} \\ &= \frac{i\sqrt{2}}{4}\sqrt{4r^2-2i^2} \\ &= \frac{i}{2}\sqrt{2r^2-i^2} \end{aligned}\]

With the two areas calculated, we now know that the area of the small purple region is the difference between the two: \[A = \frac{r^2\theta}{2} - \frac{i}{2}\sqrt{2r^2-i^2} = \boxed{\frac{1}{2}\left(r^2\theta - i\sqrt{2r^2-i^2}\right)}\]

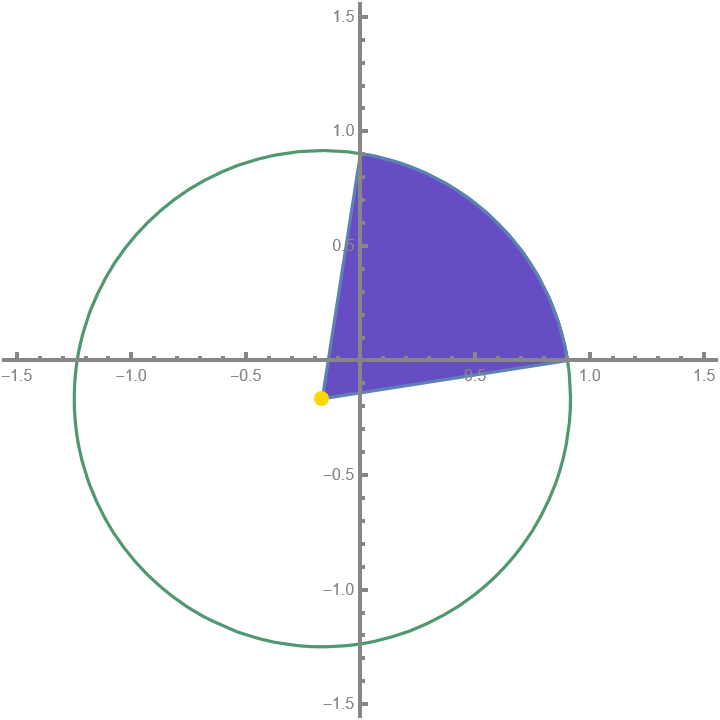

Area of the full region under the circle

The final step is to simply add the areas of the red triangle and the small purple region together and we have the area that we need! \[A = \boxed{\frac{1}{2}\left( p^2 + r^2\theta - p\sqrt{2r^2-p^2} \right)}\]

This gives just the area under one circle, but we can easily calculate this for the smaller circle. To find the actual expected value, we take the difference between the two areas. The calculations for $\theta$ and the areas stay consistent between the two circles, but $r$ and $p$ are different. We have $r = \frac{2k+1}{2k}$ and $p=\frac{\sqrt{4k^2+4k-3}-2}{2k}$ for the larger circle, and $r=\frac{2k-1}{2k}$ and $p=\frac{\sqrt{4k^2-4k-3}-2}{2k}$ for the smaller circle. Recall our expected value formula for this problem is as follows, \[\mathbb{E}(X) = \sum_{k=1}^n k(A_{\text{upper circle}} - A_{\text{lower circle}})\]

Edge case for $k=1$

There is one edge case, and that is when $k=1$. With this value of $k$, the center is at $(-1, -1)$, but its radius is $\frac{2(1)-1}{2(1)} = \frac{1}{2}$. This means the circle doesn’t even cross into the first quadrant, and its “area under the circle” is 0. However, with our formula, we get an imaginary value. With $k=1$, the expected value is just the area under the bigger circle. So during implementation, we will set it aside.

Implementation

Given that we have a formula, it is straightforward to convert this into code. Since the problem is only asking for 5 decimal places, we do not need to worry about floating point inaccuracies when calculating the arc cosine and square root.

import math

def upper_circle(k):

radius = (2 * k + 1) / (2 * k)

intercept = (math.sqrt(4 * k * k + 4 * k - 3) - 2) / (2 * k)

theta = math.acos(1 - (intercept / radius) ** 2)

area = 0.5 * (intercept ** 2 + theta * radius ** 2 - intercept * math.sqrt(2 * radius * radius - intercept ** 2))

return area

def lower_circle(k):

radius = (2 * k - 1) / (2 * k)

intercept = (math.sqrt(4 * k * k - 4 * k - 3) - 2) / (2 * k)

theta = math.acos(1 - (intercept / radius) ** 2)

area = 0.5 * (intercept ** 2 + theta * radius ** 2 - intercept * math.sqrt(2 * radius * radius - intercept ** 2))

return area

maxK = 10 ** 5

total = upper_circle(1)

for k in range(2, maxK + 1):

total += k * (upper_circle(k) - lower_circle(k))

print(f'{total:.5f}')

print(end - start, 'seconds.')

Running this relatively short piece of code, we get

157055.80999

0.16836764101753943 seconds.

Therefore, the number of points we expect to score is 157055.80999. Most of this problem was finding a formula for the area we need using some geometry rules and other area formulae.